Projects

Barista – Yakkala

Barista, Sri Lanka’s largest café chain, stands out as a recognizable name in the country’s coffee culture. This particular project is located alongside the bustling Colombo–Kandy main road and involved the renovation of an existing 3,000 sqft space, spanning both ground and first floors, into a well-planned café and restaurant with dedicated dining, kitchen, and service zones....

Read MoreThe Star House

Tucked into the lush, unhurried suburbs of Maharagama, Star House rises as a gleaming silhouette of contemporary calm—a residence where architecture speaks in hushed tones of clarity, precision, and grace. Designed for a surgeon whose profession demands an exacting eye, the home is more than a reflection of its owner’s ethos—it is the architectural embodiment of it....

Read MoreWickamaratne Group Office

The site was located in Peliyagoda 10 km away from Colombo, frontage is facing to the Colombo – Negambo main road and Kelani River, is forming the rear boundary....

Read MoreThe Triangle Residence

“The TRIANGLE,” designed to meet the needs of a contemporary family, is a modern and robust architectural design featuring simple geometric volumes that culminate in a minimalistic and highly functional home. This house is designed on a challenging, triangular-shaped, sloping plot of 12 Perches (303sq.m.) land. The existing sloping terrain is meticulously integrated into the design by incorporating a central courtyard and a connecting bridge to m...

Read MoreDharma House

The land is situated a kilometer distance from the heart of Jaffna. The land transferred generations to the client 30 years back. He migrated and lives in Australia for the last three decades. His wise to build a house in the native place as healing for bitter memories of the house destroyed in the civil war....

Read MoreThe Trees Boutique Hotel

Nestled on a serene hill overlooking the iconic Kandy Lake and the sacred Sri Dalada Maligawa (Temple of the tooth relic of the Buddha) in Sri Lanka, “The Trees” is a 27-room boutique hotel epitomizing tropical modernism and sophisticated minimalism....

Read MoreSri Lanka Institute of Nanotechnology – Phase One B

SLINTEC Phase One located at The National Nanotechnology Park in Homagama Colombo, was one of the initial projects in 2012 that catalyzed the knowledge city concept that the area is now becoming. It paved way to many modern architecture in the context to rethinking and redefining architecture of past, to look into the future with open eyes. SLINTEC is the one of the leading research institute in Sri Lanka for Science and Technology under the Mini...

Read MoreSanthanabhavanam

This personalised residence stands as a heartfelt tribute to a late mother’s enduring wish to keep family roots alive in Jaffna. The contemporary design of this home blends tradition and modernity, drawing inspiration from the textures, spatial idea, and symbolism of traditional Jaffna architecture. This residence distinguishes itself from the surrounding built fabric as a space that embodies memory, continuity, and cultural connection....

Read MoreArticles

How Traditional Sri Lankan Textiles Shape Modern Contemporary Interiors

Seamlessly connecting the island’s craft heritage with modern evolving contemporary design sensibilities, Sri Lankan textiles have stood in the forefront due to its adaptation abilities, transformative potential and aesthetic perceptions in the field of interior design....

City of Dreams

Once known primarily as a port city, Colombo has long been shaped by trade, colonial influence and its position along vital Indian Ocean routes. Over time, that maritime identity has given way to a new role as a commercial and financial center looking to establish itself within the region. This evolution is written into the city’s skyline, which in recent decades has begun to rise taller and bolder....

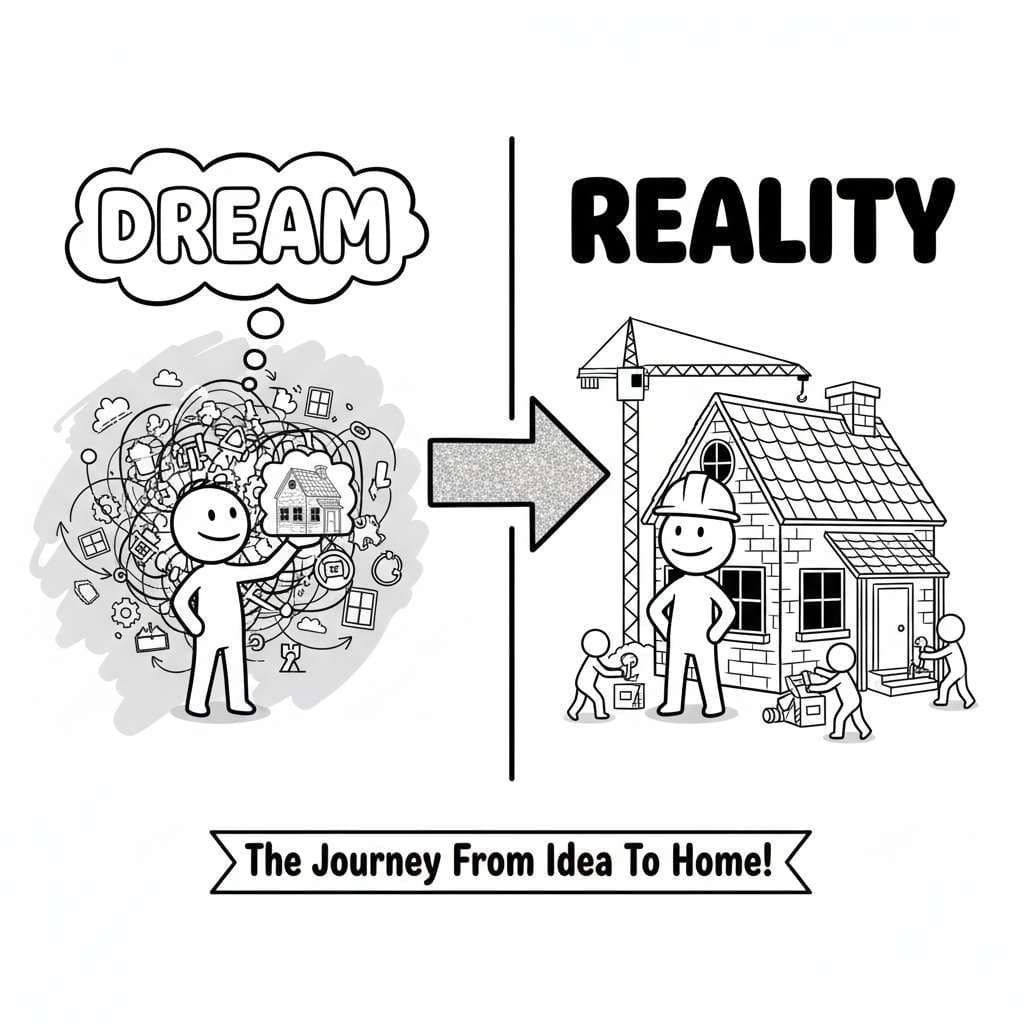

“From Dream to Reality” – The Sri Lankan Building Process

Have you ever wondered what it really takes to build a house or a building in Sri Lanka? Many people think it’s as simple as buying land, hiring a mason, and starting construction. But in reality, the journey is far more structured and when done right, it saves time, money, and endless frustration....

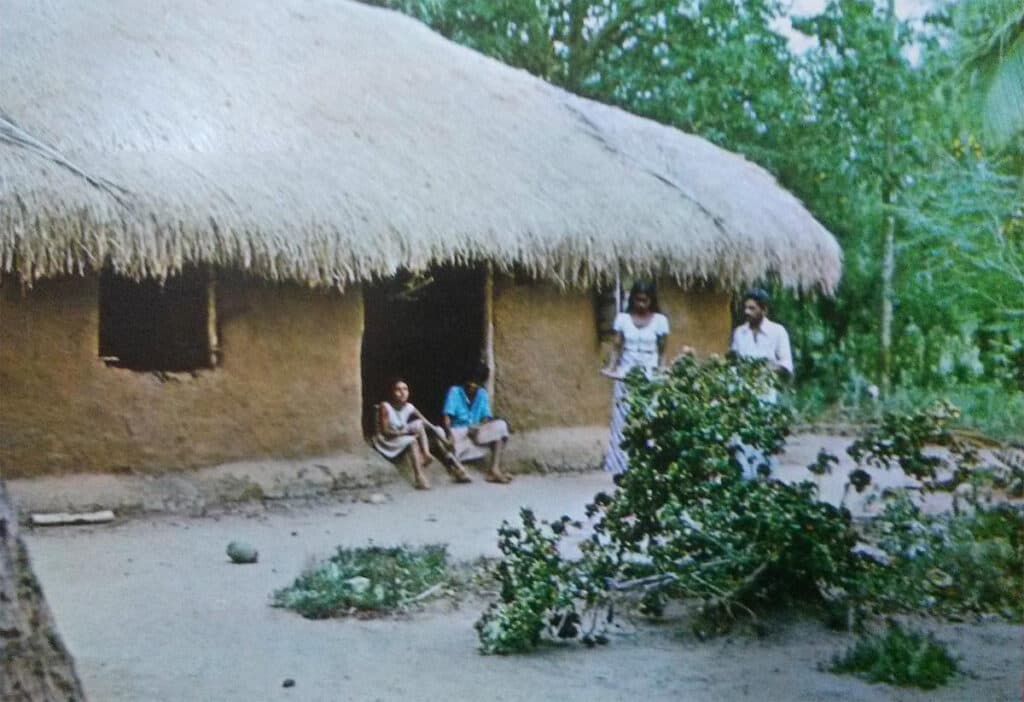

Why Sri Lankans Love Verandahs

From ancient raised “pila” in traditional vernacular mud houses to “front porch” in colonial era Walawwa type homes, the verandah is a highly significant design feature seen in Sri Lankan houses- even amongst local contemporary architecture....

Why Old Sri Lankan Houses Always Felt Cooler?

Despite the earliest evidence of thermal regulation in ancient civilizations being discovered in Rome, Sri Lankan traditional houses provided a pivotal insight into ancient human settlements- especially in terms of ancient techniques of keeping their houses cooler....

Interstice – Where Architecture Meets the In-Between

Final Year Exhibition of the University of Moratuwa On the 19th and 20th of August, the final year architecture students of the University of Moratuwa showcased their work in an exhibition – Interstice – held at Havelock Mall. The exhibition featured a few selected thesis projects of the class, with students on hand to guide […]...

News

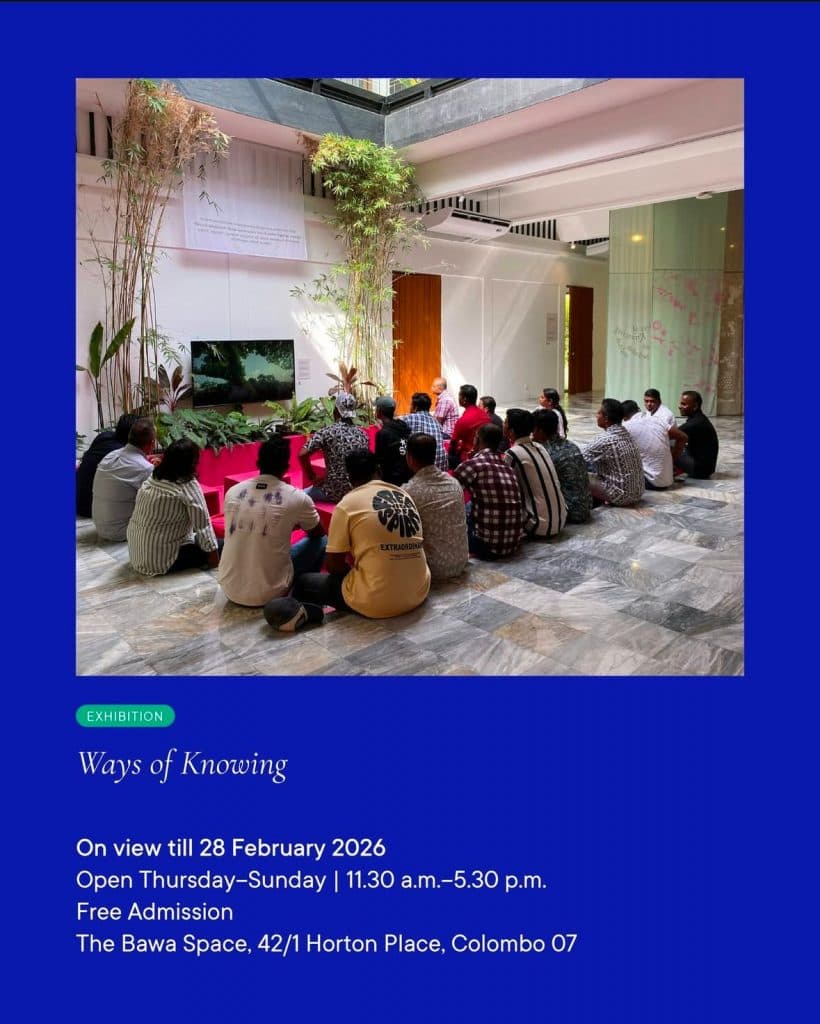

Ways of Knowing

Organized by the Geoffrey Bawa Foundation, “Ways of Knowing” is a multi-sensory exhibit and a series of guided tours which explores how multiple mediums determine how we learn, store and share our encounters and experiences- ranging from virtual reality and films to maps and textiles....

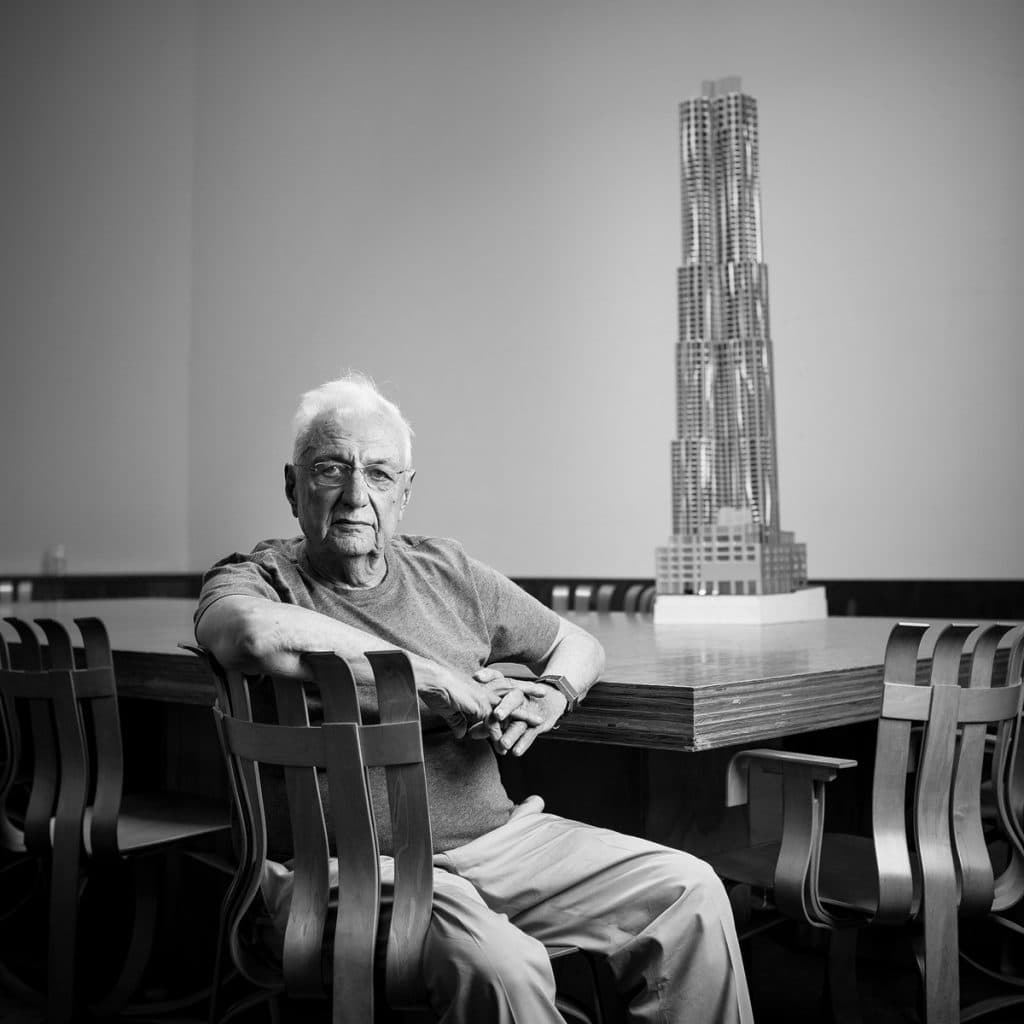

Frank Ghery Passes at 96

The visionary architect behind some of the world’s most iconic contemporary buildings, Frank Gehry has passed away at the age of 96....

Benches, Barriers and Belonging in Colombo

Celebrating the opening night of Open House Colombo 2025, “Benches, Barriers and Belongings in Colombo” is a thought-provoking discussion with the founder and director of Colombo Open Lab: Iromi Perera....

Open House Colombo

Celebrating the city’s vibrant and creative population, Open House Colombo 2025 is a festival organized by the Geoffrey Bawa Foundation, offering 2 days of behind-the-scenes tours and activities spanning over 20 locations across Colombo....

Sri Lanka Design Festival (SLDF) 2025

Launched by the Academy of Design (AOD) in 2009, Sri Lanka Design Festival aims to showcase the island’s creative industries and newly emerging talents each year- through exhibitions, fashion shows, conferences and cultural showcases....

Usher Costume Design Competition

Open to all architects and design undergraduates, the Usher Costume Design Competition is an event organized by the SLIA for the “Architect 2026” National Conference. Following the theme of “Architect in Time” the competition invites individuals and groups to design the usher costume for the even...