Valentine Gunasekara’s Modernist Vision

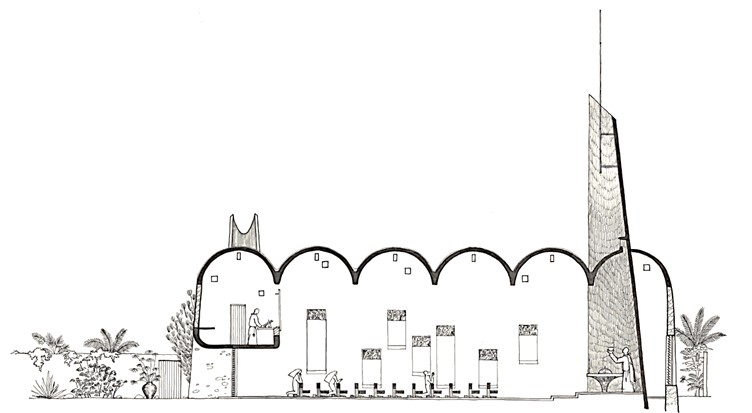

Front Facade of Jesuit Chapel © sevenby3

Post-independence Sri Lanka’s architectural landscape was shaped by nationalist and tropical regionalism, and Architect Valentine Gunasekara’ modernist works were marginalized as anti-thesis for the former. Rejecting traditional forms, he embraced spatial fluidity, often experimenting with materials like glass and reinforced concrete, advocating for redefined outward reaching designs. His work can be understood as an attempt in exploring new spatial possibilities through modern materials, addressing the needs of Sri Lanka’s emerging middle class with modernist forms. He disliked the perpetuation of what was interpreted as elite forms and aesthetics in traditional manors and colonial bungalows.

Unlike Geoffrey Bawa, who embraced regionalism, Valentine Gunasekara experimented with geometric forms, such as cones and prisms, and introduced flat and terraced roofs, influenced by the international modernist movement. His use of concrete was both a stylistic choice and a response to resource limitations and limited labour skills. His collaborations with engineers and local masons bridged high-modernist ideals with local construction methods.

While brutalism was often associated with institutional and large-scale buildings, he refined it for residential use in local context. Yet Gunasekara was aware of the Lankan tradition of houses being in dialogue with the nature, and rather than rejecting this idea, he adapted it through a modernist lens. This is evident in his house projects where he brings a balance between functionality and nature. A strategy he used to attain this was to wrap the site periphery with the building, resulting in central courtyards as breathing spaces. In his earlier projects such as Jayakody House and Munasinghe House, centered around a courtyard, a hallmark tradition of Sri Lankan dwelling, ensuring passive cooling while at the same time using sharp geometric forms and raw concrete facades in creating spatial sequence. At first glance, the house presents itself as a monolithic structure but his expertise in volumetric play is evident in the way double-height spaces and voids create a sense of expansiveness within compact footprint. But this also helped him to use repetitive elements, especially in the structural aspects which also helped maintain the building costs.

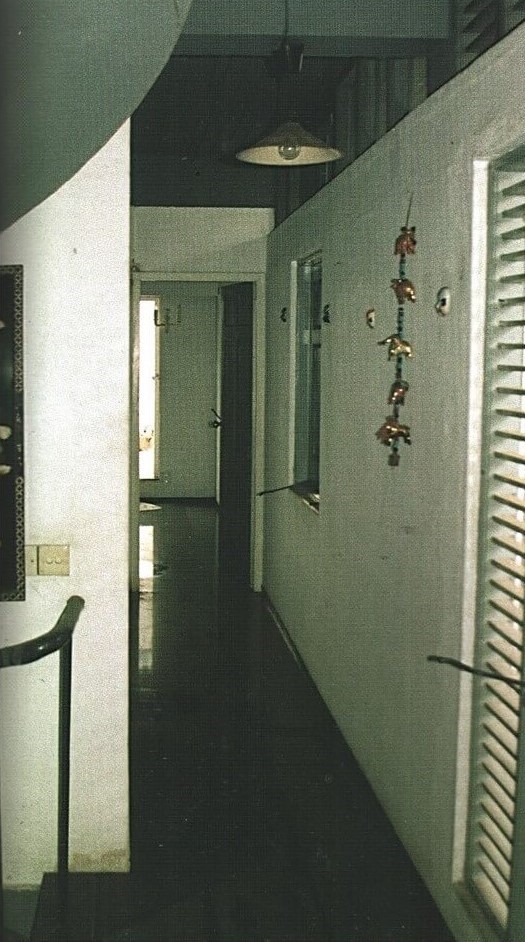

Dissolving the built form into nature © D. Perera & R. Pernice

Illangakoon House was another project where he translated his philosophy into residential works. Commissioned by a progressive family that sought a home breaking free from traditional compartmentalized layouts. The house utilized large openings and shaded verandahs to dissolve the boundaries between built form and nature, allowing the tropical landscape to be an integral part of the experience. A striking cantilevers slab appearing to hover over the landscape, one of the most defining element of the house became a symbolic representation of his ability to merge engineering and design. It was a home designed for modern living in a tropical setting embodying Gunasekara’s belief in progressive climate responsive architecture.

The hovering slab extending the landscape © M. N. R. Wijethunge

The shared Verandah – Illangakoon House © M. N. R. Wijethunge

While his initial projects still used pure tropical modernism elements, the latter projects fully emphasized on technological elements to form spatial and volumetric containers. His form making utilized the practical use of concrete structure to make spaces suited to local contexts.

The Jesuits Chapel, one of his most prolific projects emerged from a commission that sought to create a spiritual space reflecting a contemporary ideals rather than the historical precedents. Gunasekara who had studies modernist religious architecture in the West, saw an opportunity to break away from the decorative tendencies of past ecclesiastical buildings. The chapel built in raw concrete embraces brutalist ethos, yet its spatial arrangement and interplay of light elevates it to a deep contemplative space. Strategic openings punctuate the heavy concrete walls, allowing concrete walls allowing shafts of natural light to animate the interiors, very similar to Le Corbusier’s Notre-Dame in Ronchamp. The starkness of the material is softened by the way shadow and light interact in the space. The minimal yet the symbolic composition reflect the architect’s belief in honest construction where each element has a clear purpose.

The volumetric play from double height space and voids © MoMA

In contrast to the Chapel, St. Anthony’s Montessori, Borella was one project where Gunasekara attempted to generate playful yet functional spaces, breaking away from the rigid monolithic forms. The Montessori’s spatial composition is open and fluid with courtyards, shaded walkways and semi-open play areas that encourage movement and exploration. The material palette of concrete, timber and glass was deliberately kept simple, while the use of playful colours induced curiosity in the minds of the children, reinforcing the Montessori philosophy of natural learning environment.

Present state of St. Anthony’s Church in Borella © Midcentury.blogspot

The 1960s also saw a rise in tourism with most hospitality projects drawing from colonial or indigenous architectural languages. However, Gunasekara envisioned something entirely different: a brutalist geometric intervention that would integrate into the dramatic coastline of Tangalle. The repetition of triangular modules not only maximized efficiency in prefabrication but also created dynamic interiors. As the local builders were accustomed to conventional rectilinear spaces struggled with the unusual geometry, which meant the project was developed through rigorous site supervisions and robust problem solving by the architect.

The once active Tangalle Bay Hotel © President medal

The ruined state of Tangalle Bay Hotel © martino.stierli.insta

Valentine Gunasekara’s modernist stance was not a mere importation of Western ideas but an adaptation that responds to the local context. His work exemplifies what could be described as “critical cosmopolitanism” by Anoma Pieris, a stance that moves beyond the binaries of international modernism and vernacular architecture. Unfortunately, his work was often met with resistance, as he constantly challenged the ingrained tradition. Most of his works are also either in depleted state or non-existent now. Yet, his vision endures, with the work remaining inspiring architects grappling with the intersection of modernism and regionalism.