Minette De Silva

The unsung pioneer of Critical Regionalism in Sri Lankan Architecture

Minette de Silva at the 1948 World Congress of Intellectuals in Defence of Peace © The Guardian

After years of struggle Sri Lanka was embracing decolonization after gaining independence from British rule during the mid-20th century. This was reflected in many aspects of daily life and Architecture and built environment was also in a phase of reviving and rejuvenating of traditional identities. Minette De Silva was one architect who played a significant role in Sri Lankan Architecture during this period. Having studied and worked in India and London she was also a modernist at heart. This fusion led to a practice blending local materials, techniques and artisanal traditions with the principles of modernism. This article discusses five significant projects handled by Archt. Minette De Silva during this transformative period.

Karunaratne House, Kandy (1951)

Karunaratne House marked the beginning of De Silva’s architectural journey and philosophy. Commissioned by family friends, this villa was more than a home—it was a canvas for De Silva’s vision of blending modernist principles with Sri Lankan identity. Drawing inspiration from her studies and exposure to global modernism, she emphasized local materials and craftsmanship, hiring artisans to create Dumbara mat panels, clay tiles, and incorporating art by local artists. De Silva’s involvement was hands-on; she worked closely with craftspeople to ensure cultural authenticity while experimenting with space and climate-responsive design. This house became a prototype for her Critical Regionalism ethos, making a profound statement about modernity and tradition in post-colonial Sri Lanka.

Karunaratne House, Kandy © Suravi

Pieris House, Colombo (1956)

Designed for the Pieris family in Colombo, the house introduced the meda midula (central courtyard) into modern living spaces, a reinterpretation of traditional Sri Lankan architecture.

De Silva incorporated handcrafted elements such as limestone walls and artisanal finishes utilizing local craftsmanship. Considering Colombo’s tropical climate, there is an integration of cross ventilation and open courtyards for cooling. This project is a precedent of cultural preservation in a modern regionalist architecture, and inspired figures like Geoffrey Bawa.

Loggia looking through the Courtyard in the Pieris House © The Architectural Review

Senanayake Housing, Colombo (1950)

This project is a modernist response to the challenges of urban living in post-independence era. Designed as a multi-story building, there are traces of European modernism translated to local context. The approach is based on the strategic planting around the building, softening the strong modernist exterior and providing natural cooling. The whitewashed building, though minimal in design, was influenced by Le Corbusier’s modernist ideals, but De Silva’s use of landscaping and climate-responsive elements set it apart, showcasing her ability to merge modernism with local needs.

Senanayake Flats in Colombo © Three Blind Men

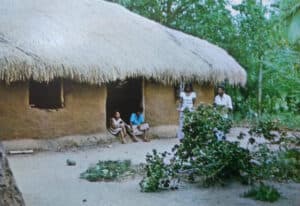

Watapuluwa Housing scheme, Kandy (1960s)

Designed for public servants, the project emphasized functionality and community engagement and was a major prototype for affordable housing in Sri Lanka. To ensure developing lively homes, De Silva involved future residents in the design process, ensuring the homes met their needs. She incorporated local building techniques, such as rammed earth and traditional vernacular forms, to create cost effective and climate responsive homes. The resulting layout fostered a sense of community enhancing social interactions. The project reflected De Silva’s commitment to sustainable and participatory design, becoming a model for future public housing in Sri Lanka.

Ariel view of the current state of Watapuluwa Housing scheme © Ines Leonor Nunes

Art Centre, Kandy (1984)

Kandy Arts Centre, completed in the 1980s, was a culmination of her architectural evolution, blending modernist design with Sri Lankan tradition. Contrary to her previous works, here she attempted utilising modernist ideals in different ways. The original structure was maintained, using local stone, wood and traditional construction techniques while introducing modern structural elements. The design harmonized with the surrounding landscape, emphasizing natural light and ventilation. The Kandy Arts Centre which remains as her final completed project, reflected her mature style, balancing preservation with innovation and strengthening the connection to Sri Lanka’s cultural identity.

Arts Centre, Kandy © Architectural Review

De Silva was a pioneer in critical regionalism in Sri Lanka, emphasizing the importance of community, climate and crafts in her designs. The integration of traditional elements into spaces, creating buildings that were both modern as well as rooted in local context is consistent in all her projects. Despite her pioneering contributions, de Silva’s work never received the recognition it deserves with her influence often overshadowed by later contemporaries but nonetheless, her legacy remains integral to Sri Lanka’s Architectural evolution.

Lunuganga by Geoffrey Bawa

Essential Tips for Designing a Comfortable and Low – Maintenance Washroom

Related Posts

How Traditional Sri Lankan Textiles Shape Modern Contemporary Interiors

November 12, 2025

City of Dreams

October 22, 2025

“From Dream to Reality” – The Sri Lankan Building Process

October 8, 2025

Why Sri Lankans Love Verandahs

October 1, 2025

Why Old Sri Lankan Houses Always Felt Cooler?

September 10, 2025

Interstice – Where Architecture Meets the In-Between

September 3, 2025