Climatic Resilience Through Architecture

Resilience is the capacity to recover from a challenge, an inherent quality of endurance. It is a broad term that applies to people, buildings and landscapes. With regard to architecture, resilience is the ability of a building to resist or prevent damage or to recover from damage. This is critical for a building in a precarious context.

There are different types of resilience; the ability to weather economic, climatic changes, adaptability to new purposes and flexibility to repairs or reuse. Whether a building is able to thrive over time, serving new functions without becoming redundant is also resilience. These are buildings that support the local community so that they can thrive despite social, economic or environmental stressors.

Climatic resilience is critical in a high risk region, as building failure can have severe consequences on the community and surrounding infrastructure. Collapsing structures can lead to deaths, economic loss and environmental degradation. In this article, we will be focusing on the physical aspect of building climate resilience.

Flooding in Brazil © Gustavo Mansur

Need for resilience

Resilience doesn’t need to be a priority when designing every building. It is very much context dependent. It should be prioritised when building in high risk regions prone for natural disasters as well as critical infrastructure, public buildings and high value buildings. Public buildings such as community centres and schools can be used as emergency shelters in the aftermath of a disaster. High value buildings can have a historical, cultural or financial aspect; these are vital landmarks in the built fabric.

The life expectancy of the structure can give an idea of the need for resilience. Temporary buildings or housing doesn’t necessarily need to be resilient. For example, if building in a region with a low risk for natural disasters, affordability and energy efficiency can be prioritised over resilience. However, while many of the future natural disasters and extreme weather in a location can be predicted creating the basis for resilient design, climate change and global warming have added an element of unpredictability. Some new challenges to consider are rising sea levels, intense rain storms and persistent droughts.

Natural disasters and extreme weather

In the aftermath of a disaster, the building needs to have the capacity to withstand or adapt to changes. The approach to resilience starts from the design stage. The local environment, weather and disaster histories will give an idea of the climatic stressors to be considered.

LOG shelter © Heritage Foundation of Pakistan

A programme to help communities become resilient through flood resistant housing was launched by architect Yasmeen Lari in Pakistan; it further focuses on social and economic resilience. The shelters built during the emergency phase will be later converted to permanent structures. These are built with local materials and require no special skills. Elevated prefabricated bamboo structures, aquifer wells, forest and bamboo barriers etc. are used to prepare for future floods. This shows that climatic and community resilience can be achieved with low cost materials and approaches.

Elevated structures to stay above floodwaters © Heritage Foundation of Pakistan

Resilience planning

Once the impact of climate and weather on a certain site is understood, building orientation and layout needs to be worked out. There are several ways of countering a physical attack to the structure such as the use of technology for surveillance and warning systems, physical approaches such as setting back the building, access routes for emergency personnel and evacuation, building material selection as well as planning operational processes. Combined, these strategies can pose a formidable front of protection.

© Bruce Damonte

The Ray and Dagmar Dolby Regeneration Medicine Building by Rafael Viñoly Architects achieve seismic base isolation through its space truss supports resting on concrete piers. This approach allows the structure to absorb earthquake forces.

© Bruce Damonte

To ensure that building operation continues in the aftermath of a disaster, critical utilities and backup systems should be located in defensive locations. This allows for rapid recovery of services. The condition of surrounding infrastructure and utilities will significantly affect the resilience of the building. It is difficult to maintain resilience when there are extended power and utility shortages. In such a region, a building with self-sustaining operations and services will be able to hold out longer; this will need a larger initial investment. The decision to do so will depend on the core functions of the building and its importance to the community.

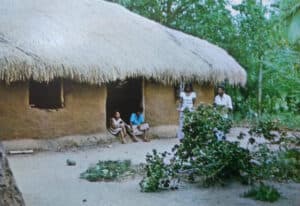

However, physically strengthening a building is only one way of becoming climatically resilient. Another approach is designing certain building elements such as roofs, walls etc. so that they can give way when facing high winds, floods or other natural disasters. This can help minimise damage done to the building making it easier to recover. Permanence is not an essential factor for resilience.

© Emily-Jane Proudfoot/ Shutterstock

Ganvie is an African village that is floating in the middle of a lake. Houses are built on wooden stilts while public buildings rest on concrete stilts. Locals focus on materials that decompose in the water system; the structures have a maximum lifespan of 20 years.

Passive and active measures

Passive design features can mitigate threats while active measures can mount a response. Passive design features like fencing, curbs and barriers can control access to the site while critical systems can be located in low risk areas within or around the building for maximum protection; exterior infrastructure can be carefully anchored in place. The façade of the structure can also be strengthened to withstand impact through structural hardening. For passive flood protection, water retention ponds, permeable surfaces and underground reservoirs can be used.

The Parque Rachel de Queiroz © Joana França

The Parque Rachel de Queiroz project in Brazil by Architectus S/S provides a solution to flooding by preserving and developing existing wetland areas with the creation of a public park. Nine interconnected ponds help provide flood dampening and water filtration. Pathways around the ponds lead to public facilities such as sports courts, an outdoor gym, a dog park and an amphitheatre.

Active measures include the use of security and monitoring systems, backup communication systems and emergency power such as standby generators and fuel storage on-site. Sump pumps and automatic drainage systems can be used as active flood protection especially in areas with critical systems.

Look to the Future

The decisions made regarding development of urban areas trickle down to the development of single sites. These major decisions can affect the risk factor of the region. This highlights the need to provide a comprehensive solution to urban planning. In addition to creating climatically resilient architecture, it will contribute to safe and stable communities.

Related Posts

How Traditional Sri Lankan Textiles Shape Modern Contemporary Interiors

November 12, 2025

City of Dreams

October 22, 2025

“From Dream to Reality” – The Sri Lankan Building Process

October 8, 2025

Why Sri Lankans Love Verandahs

October 1, 2025

Why Old Sri Lankan Houses Always Felt Cooler?

September 10, 2025

Interstice – Where Architecture Meets the In-Between

September 3, 2025