The Lesser-known Architectural Works of Geoffrey Bawa

‘A Home by the rolling Billows’ St. Thomas’ Preparatory School, Kollupitiya ©Lunuganga Trust

Geoffrey Bawa, the celebrated Sri Lankan Architect is known for his works centers around Tropical Modernism. While many of his works are well known and highly celebrated, some of his profound projects do not stand on that pedestal. They rarely make it to magazine covers or serve the curated sunset views. Some sit quietly behind school walls, some sit by calm lakes and some sit on edges of industrial or commercial fabric, woven into rhythms of daily life. Yet these works also celebrate spaces like any other of Bawa’s work: Corridors are not passages but slow transitions, courtyards hold not grandeur but pause, and walls that connect indoor and outdoor. This article dives into five such projects which are the lesser-known whispers.

The sacred simplicity of spaces at St. Thomas’ Preparatory School, Kollupitiya (1968)

Tucked away in a highly urbanized part of Colombo, St. Thomas’ Prep. School is one of Bawa’s most underappreciated institutional works. Though compact, the school complex is a brilliant example of climate-responsive architecture in urban plots. Instead of monolithic institutional blocks, Bawa designed it as a series of low-rise classroom blocks around a central court and avoids the rigidity of typical school buildings. There is a fluid walkable network around the school blending instruction with contemplation.

The buildings use thick brick walls, clay tiles roof (now replaced) and open-air corridors designed as thermal buffers. Natural cross-ventilation is enhanced by raised rooflines and operable timber louvres, sadly now removed. Verandahs are strategically placed to be extension of classrooms and informal learning spaces. Trees punctuating the courtyard, add to the spatial rhythm. Overall, the proportion of the building help maintain a close-knit environment, fostering a sense of community tailored to the young minds.

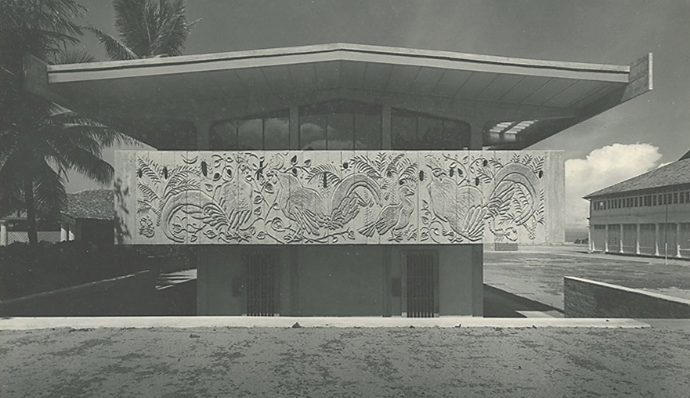

Lower school and Administrative Block then ©Lunuganga Trust

Middle class and Main Hall Block then ©Lunuganga Trust

Monastic Modernism at the Agrarian Research & Training Institute (ARTI), Colombo (1978)

Bawa’s design for ARTI showcases how modernist planning principles can harmonize with vernacular sensibilities. Commissioned as a government research and training center, ARTI consists of multiple wings around courtyards, walkways, and shaded plazas, creating a porous campus within the city. The buildings are low-slung, finished in white render and clay tile roofing, balancing modern geometry with traditional forms.

Circulation is celebrated rather than concealed: Corridors opening to landscapes, offering views, breezes, and chance encounter. A subtle hierarchy of spaces unfolds along the research rooms, lecture halls and public spaces. The transitions are executed via light filtering through brise-soleil and timber lattices. This results in not only a functional learning center, but a serene academic retreat.

Corridors opening to the landscape ©Archdaily

Play of forms at the entrance ©Archdaily

Transit in silence at the Bentota Railway Station (1980s)

While most railway stations in Sri Lanka follow colonial or utilitarian templates, the Bentota station redesigned by Bawa offers an architectural surprise. It transforms a functional node into an experience of place. The design still utilizes minimal interventions and maximum spatial qualities.

The platform shelter was designed with low-pitched tilted roofs, exposed timber trusses and a generous overhand to create the shade. The waiting areas are not enclosed boxes but open pavilions that embrace breeze and light. Planters, benches and decorative screens subtly insert warmth into the transit experience. The platform edge is treated like a verandah, where one can linger, converse and observe the rhythm of daily life. Even while sitting in a setting of temporal flow and public noise, the space celebrates stillness, shadow and familiarity, while not dominating the context.

Platform as open pavilions mingling with light and silence ©Vacaywork

A silent transition ©Dreamstime

Interwoven Landscape at Club Villa, Bentota (1979)

A conversion of an old colonial residence into a boutique guesthouse, Club Villa exemplifies Bawa’s belief in the power of small, considered moves. The layout is intimate: a layered sequence of courtyards, verandahs, gardens and open lounges that conceal and reveal spaces gradually. The layout is such that you never see the whole building at once.

Interior spaces borrow from residential language of Bawa: whitewashed walls, timber detailing and polishes floors creating a domestic homely experience. The gardens become the protagonist with frangipani trees and narrow water channels shaping the views. There is no grand arrival, instead the entry is modest and almost secretive. The transitions are orchestrated focusing on light, temperatures and material that makes the architecture feel discovered rather than presented.

The garden as the protagonist ©The Hotel Guru

From a hotel to a home ©Experience Travel group

Where time slows down at Anuradhapura Rest House (1982)

Rarely published and now mostly forgotten, this retreat was designed for pilgrims of the sacred city is a cluster of low, tiled roof pavilion. Sited by the Anuradhapura, the building reflects Bawa’s restrained modernism with deep sensitivity to context and context. It’s not luxury but about ease, stillness and dignity.

The plan is horizontal, stretching across the site to maximize the views and allow gentle breezes to pass through. Bedrooms open to shaded verandahs while communal spaces are centered around the courtyard filled with trees, birds and filtered light. Materials are muted: coral stone walls, timber doors and clay tiles. The architecture cuts the outside rush and effectively slows down time.

Modern yet simple ©Sebastian Posingis

Many of these building may not seek attention, but they hold it gently and enduringly. They reveal as architect who listened more than he imposed, often trusting silence as much as forms, thus a reason for not capturing much attention. Many of these quitter works are now heavily changed on non-existent, these whispers into margins where architecture less about statement but more about condition.