Despite the earliest evidence of thermal regulation in ancient civilizations being discovered in Rome, Sri Lankan traditional houses provided a pivotal insight into ancient human settlements- especially in terms of ancient techniques of keeping their houses cooler.

For a tropical country with a 28-30 °C average temperature, and a culture with a way of life deeply integrated with nature- it is undeniable that Sri Lankan vernacular architecture embraces a variety unique and nature-friendly passive cooling strategies.

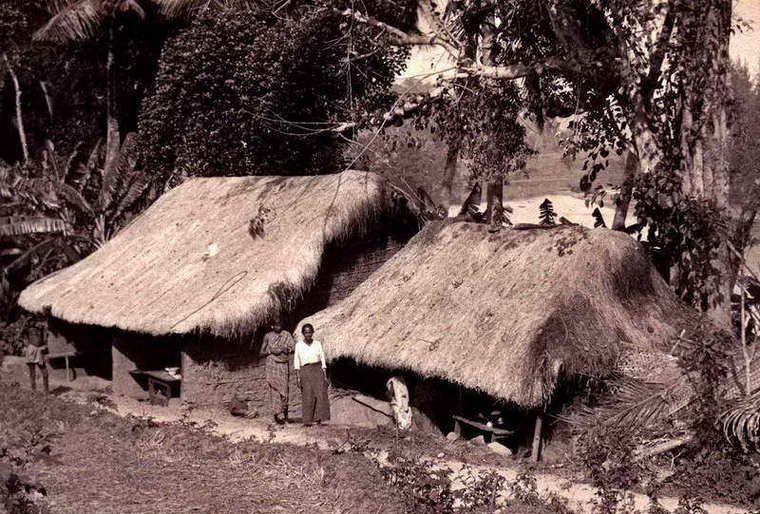

Fig 1- A rustic Sri Lankan clay-thatch house in 1980s

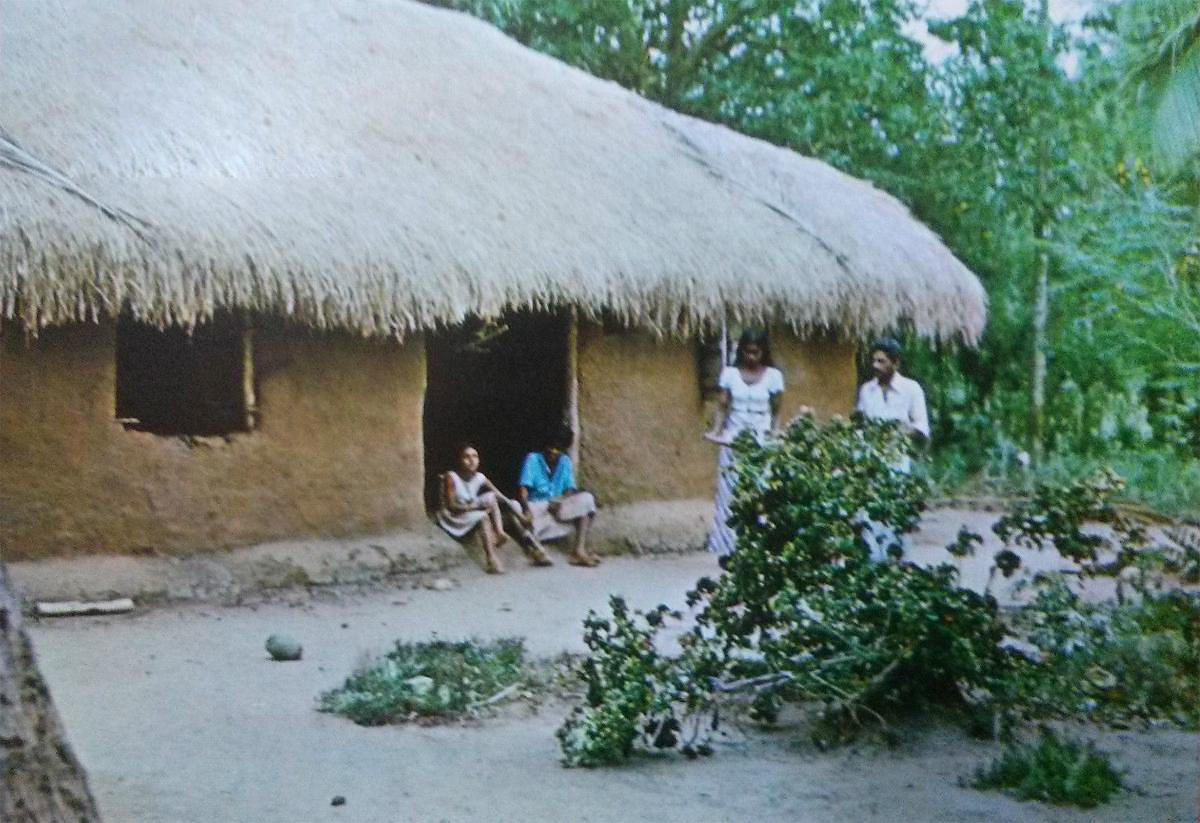

Walls and floors being constructed from locally available, high thermal mass materials are one of the predominant features of ancient homes. High thermal mass materials have a unique property where they have the ability to absorb heat during the daytime and slowly release the stored heat energy at night.

Mud, laterite stone, clay and wattle were the most common walls and floor finishes. Upon the discovery of lime plaster, ancient houses began to incorporate them into the interior walls of the house as a finish as well, to make the space more breathable.

Fig 2 – Construction of wattle walls with a framework made from locally sourced sticks, and inserting a clay-mud mix into the voids

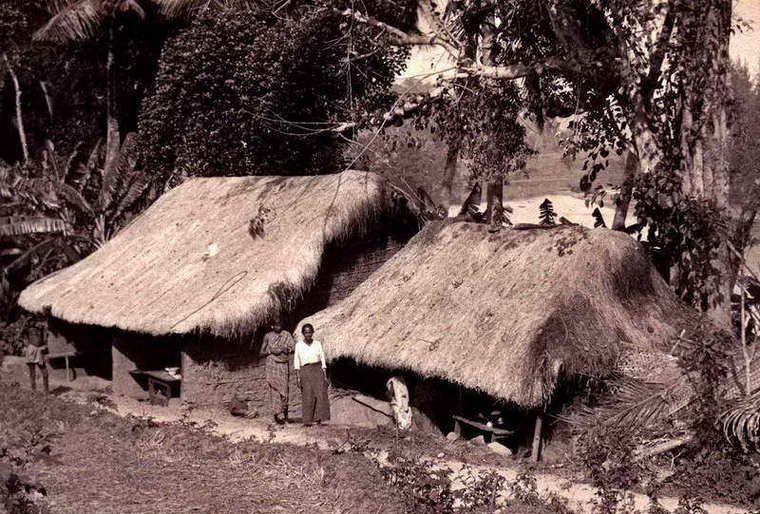

The roofs- in terms of its pitch angle and the materials used, is yet another important architectural consideration in ancient Sri Lankan houses. Here, the based cooling technique is referred to as ‘evaporative cooling’, where the absorbed heat is released back through evaporation.

Ancient homes typically included a gable or a hipped roof shape with a high degree of slope to allow hot air to escape quickly. Additionally, the high slope resulted in a high ceiling height, which improved stack ventilation- a phenomenon where the hot air rises from lower areas and cooler air flows through the living space. They were constructed from locally sourced organic materials such as straw, coconut leaves, timber and clay tiles.

Fig 3 – Exterior view of ancient, thatched roofs

Fig 4 – Roof constructed from tying bamboo sticks with ropes and attaching woven coconut leaves

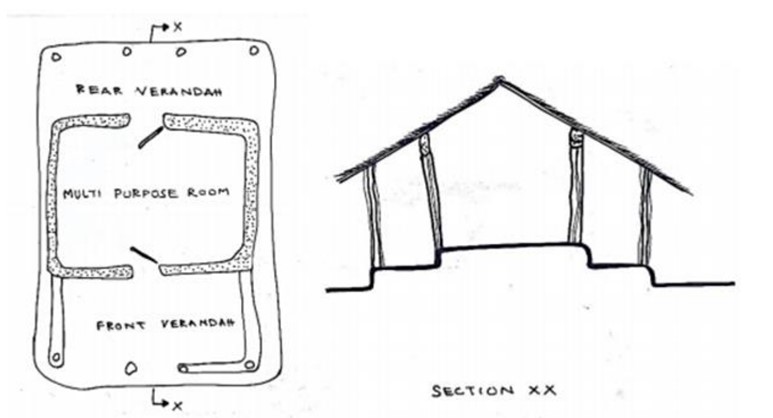

In terms of spatial planning, one of the most notable characteristics of ancient Sri Lankan houses was the incorporation of wide “verandahs”, shaded by deep overhangs. This provided 3 advantages- shading the main interior spaces from harsh sunlight, acting as a thermal buffer (intermediate) zone, and allowing for cross breeze through the house due to changes in temperatures.

Fig 5 – Deep eaves and wide verandahs cool the interior spaces

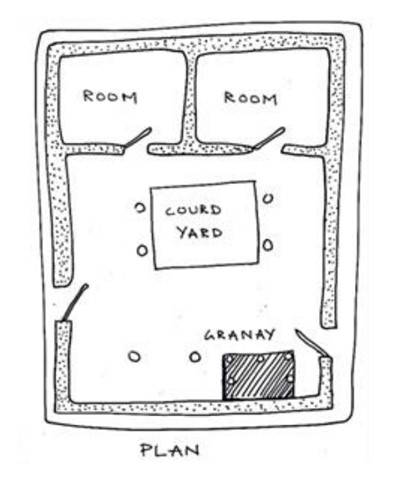

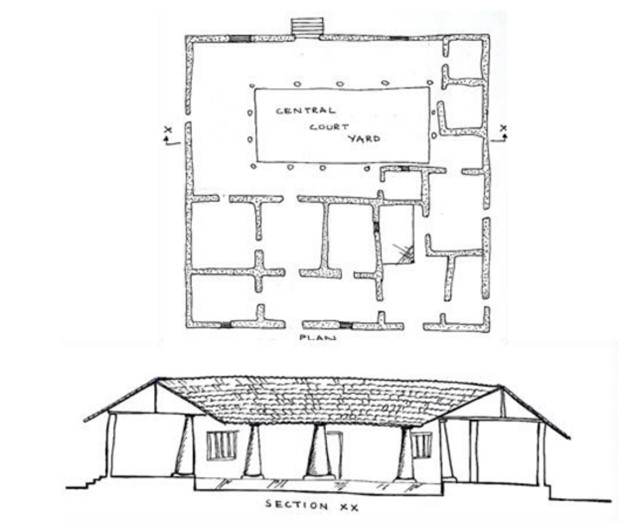

One of the most notable architectural features of Sri Lankan houses- especially Kandyan houses is the formation of “courtyards”, which is an interior space fully enclosed from the sides but fully open to the sky. Not only did this provide an interior garden for the house, but it also allowed the houses to open their windows to the inside instead of the outside, further cutting down the harsh sunlight and additionally cooling the space.

Courtyards also acted as natural cooling wells- letting the hot air escape upwards without storing it within the interior.

Fig 6 – Plan of an ancient traditional courtyard house in Kandy

Fig 7 – Plan and section of a Kandyan “Walawwa” type house with an internal courtyard

With these vernacular architectural characteristics, ancient Sri Lankan homes have simply but successfully managed to thermally regulate their internal spaces, without the need for mechanical means- further proving that nature itself could be the possible blueprint for sustainable local constructions.

Reference:

https://dl.lib.uom.lk/server/api/core/bitstreams/eee337af-3c93-461b-a90f-ff87e6fdeb25/content

https://brunyfirepower.wordpress.com/2013/12/01/sri-lankan-sojourns-building-with-clay/