People and places are always intertwined; the human component of architecture is what breathes life into it, bringing character and purpose to the structure. In community-centric design, there is deep exploration into what makes a certain community unique; their dreams, aspirations and needs are a crucial building block to design. This is what highlights the contrast between community-centric and individual-centric design; the former revolves around the needs of the community while the latter revolves around the needs of an entity.

Participatory Design

La Borda housing, Barcelona © Lluc Miralles

Another aspect of community-centric design is participatory design. This is where the end users are involved in the design process, giving them greater autonomy over their own environment at a larger scale. Their engagement leads to them being responsible for their environment; it fosters community ownership and identity. This ownership creates an emotional connection that encourages people to care for the space, preserving it for the future. An example of participatory design is La Borda housing in Barcelona where each resident actively contributed to the building design, function and management. The shared spaces including kitchen-dining, laundry, visitor room, health and care spaces envelope a central courtyard which is the primary gathering space of the residents. The gap between the community and the built environment is thus bridged through shared values, needs and active participation.

La Borda housing, Barcelona © Lluc Miralles

Community Wellbeing

Community-centric architecture builds on human experiences. It allows different people to interact and build new relationships. With land becoming scarce, our living spaces have become smaller and smaller. This further signifies the need for spaces we can co-inhabit with others that promote social interaction. Places where we feel welcomed and safe. These spaces help preserve the cultural heritage of the community. Community-centric design promotes community health. For example, green spaces, parks, market spaces, workshops etc. allow people to engage in physical activity. Interacting with others and taking part in shared activities promotes mental wellbeing. This connection can create strong social support networks and provide more access to local resources. Buildings and open spaces can also be designed to boost economic development of the community by accommodating local businesses and industries.

Design Aspects

There are a few considerations in creating community-centric design. Public engagement has to be prioritised so that each unique facet of the community is given a space of their own to participate and to be part of the space. This can be through community workshops, classes, markets and events. Accessibility is another factor; accessibility to people of all physical, sensory and cognitive abilities and the provision of inclusive amenities such as seating areas, restrooms, recreational spaces etc. Environmental sustainability can be thought of in terms of conserving resources and preserving environmental ecology. How the space responds to the human scale will influence walkability and social interaction.

Concordia Design © Juliusz Sokołowski

The character of community-centric spaces can be drawn from the cultural and/or historical heritage of the place. One example is the use of local art, building materials and local craftsmanship. These spaces need to be flexible so that it encompass the past, present and future lives of the people within, adapting to different uses. Collaboration between the local community, architects, experts and other stakeholders is crucial for this. Open dialogue and community representation can address cultural sensitivities and social relationships. However, the architect needs to balance the needs of the developer or client with those of the community. Oftentimes, the priority of the investors will drive project goals. It is in the hands of the architect to give insight into community needs.

Housing

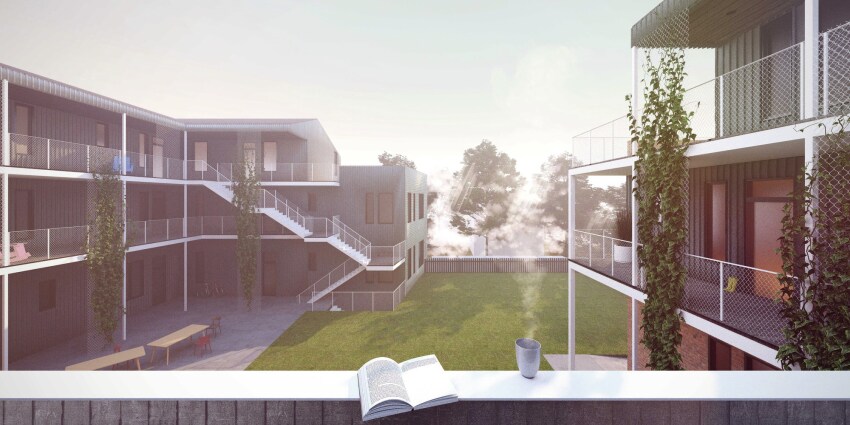

Community-centric design is not just limited to public spaces. The same approach can be followed in apartments and social housing. However, when there are no residents secured for the housing or apartment, incorporating the community element can be a challenge. In an apartment complex, the design of the building can be manipulated so as to create more communal spaces for interaction; where different families living in close quarters can become a larger cohesive unit. It all starts with understanding the users. The Bay State Cohousing model designed by French2d explored the needs of the residents by hosting several workshops. The core of this building is a large dining room with shared living and kitchen. The living units vary in size and the residents share common areas such as a craft workshop and a yoga room.

The Bay State Cohousing Rendering by Glen Marquardt © French 2D

In the case of a single dwelling, how the spaces are oriented will decide whether the occupants are part of the greater community or not. Spaces where outside noise (a combination of vehicles, pets, pedestrian voices) are allowed to filter in. Spaces adjacent to the common paths allow conversations with the occupants and the neighbours to take place. This creates a sense of awareness of where you are situated, deeply enmeshing you in the neighbourhood fabric.

Mixed-Use Developments

Concordia Design © Juliusz Sokołowski

A mixed used building can be approached through community-centric design as well. One example of this is Concordia Design, located in Poland and designed by MVRDV architects. One part of it is a renovation of an existing building preserving the historical heritage of the place. This has co-working spaces to support young businesses and an event venue. The other part is an extension with a modern twist. This houses the food hall, and is opened to the community using a three storey glass façade. This faces the public park creating a focal point for people to gather.

Food Hall at Concordia Design © Juliusz Sokołowski

Community-centric design explores the relationship of people and place, history and trends, culture and individual aspirations; it seeks to bind multiple strands together to establish an urban fabric deeply rooted in the psyche of the residents.